Behind Closed Doors the American Family S01e05 Vodlocker

| The Doors | |

|---|---|

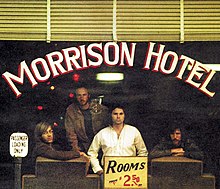

The Doors in 1966: Morrison (left), Densmore (centre), Krieger (correct) and Manzarek (seated) | |

| Groundwork information | |

| Origin | Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Genres |

|

| Years active |

|

| Labels | Elektra |

| Associated acts |

|

| Website | thedoors |

| Past members |

|

The Doors were an American rock band formed in Los Angeles in 1965, with vocalist Jim Morrison, keyboardist Ray Manzarek, guitarist Robby Krieger, and drummer John Densmore. They were amongst the most controversial and influential rock acts of the 1960s, partly due to Morrison's lyrics and phonation, along with his erratic stage persona, and the group is also widely regarded as an of import part of the era's counterculture.[4]

The band took its proper name from the title of Aldous Huxley's book The Doors of Perception, itself a reference to a quote by William Blake. Later signing with Elektra Records in 1966, the Doors with Morrison released six albums in five years, some of which are considered amid the greatest of all time,[v] including their self-titled debut (1967), Strange Days (1967), and 50.A. Woman (1971). They were one of the about successful bands during that time and by 1972 the Doors had sold over 4 meg albums domestically and nearly viii million singles.[6]

Morrison died in uncertain circumstances in 1971. The band continued equally a trio until disbanding in 1973.[7] [8] They released three more albums in the 1970s, 2 of which featured earlier recordings past Morrison, and over the decades reunited on phase in various configurations. In 2002, Manzarek, Krieger and Ian Astbury of the Cult on vocals started performing every bit "The Doors of the 21st Century". Densmore and the Morrison estate successfully sued them over the use of the band'southward name. Later on a brusk fourth dimension as Riders on the Storm, they settled on the name Manzarek–Krieger and toured until Manzarek'due south death in 2013.

The Doors were the first American band to accumulate 8 consecutive gilt LPs.[nb 1] According to the RIAA, they have sold 34 million albums in the The states[10] and over 100 meg records worldwide,[11] making them ane of the acknowledged bands of all fourth dimension.[12] The Doors have been listed as i of the greatest artists of all fourth dimension by magazines including Rolling Stone, which ranked them 41st on its list of the "100 Greatest Artists of All Time".[13] In 1993, they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

History [edit]

Origins (July 1965 – August 1966) [edit]

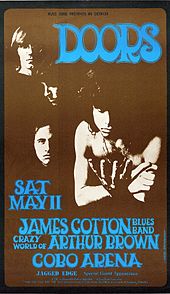

The Doors logo, designed by an Elektra Records assistant, first appeared on their 1967 debut album.

The Doors began with a chance coming together between acquaintances Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek on Venice Beach in July 1965. They recognized one some other from when they had both attended the UCLA School of Theater, Moving-picture show and Television set. Morrison told Manzarek he had been writing songs.[14] As Morrison would after relate to Jerry Hopkins in Rolling Stone, "Those first five or half-dozen songs I wrote, I was just taking notes at a fantastic stone concert that was going on within my head. And one time I'd written the songs, I had to sing them."[15] With Manzarek's encouragement, Morrison sang the opening words of "Moonlight Drive": "Let's swim to the moon, allow's climb through the tide, penetrate the evening that the city sleeps to hibernate." Manzarek was inspired, thinking of all the music he could play to accompany these "cool and spooky" lyrics.[16]

Manzarek was currently in a ring called Rick & the Ravens with his brothers Rick and Jim, while drummer John Densmore was playing with the Psychedelic Rangers and knew Manzarek from meditation classes.[17] Densmore joined the group after in August, 1965. Together, they combined varied musical backgrounds, from jazz, rock, dejection, and folk music idioms.[18] The five, along with bass player Patty Sullivan,[nb 2] and now christened the Doors, recorded a six-song demo on September 2, 1965, at World Pacific Studios in Los Angeles.[nb 3] The ring took their proper noun from the title of Aldous Huxley's volume The Doors of Perception, itself derived from a line in William Blake'due south The Marriage of Sky and Hell: "If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is: infinite".[21] [22] In late 1965, after Manzarek'southward ii brothers left, guitarist Robby Krieger joined.[23]

From February to May 1966, the group had a residency at the "rundown" and "sleazy" Los Angeles order London Fog, appearing on the bill with "Rhonda Lane Exotic Dancer".[24] The experience gave Morrison confidence to perform in front end of a live audience, and the band as a whole to develop and, in some cases, lengthen their songs and work "The Cease" and "Light My Burn" into the pieces that would appear on their debut album.[24] Manzarek later said that at the London Fog the band "became this collective entity, this unit of oneness ... that is where the magic began to happen."[24] The group presently graduated to the more esteemed Whisky a Become Get, where they were the house band (starting from May 1966), supporting acts, including Van Morrison's grouping Them.[25] On their last night together the two bands joined upwards for "In the Midnight 60 minutes" and a xx-minute jam session of "Gloria".[26] [27]

On August 10, 1966, they were spotted past Elektra Records president Jac Holzman, who was present at the recommendation of Love vocalizer Arthur Lee, whose group was with Elektra Records. Afterward Holzman and producer Paul A. Rothchild saw ii sets of the band playing at the Whisky a Become Go, they signed them to the Elektra Records label on Baronial 18 — the showtime of a long and successful partnership with Rothchild and sound engineer Bruce Botnick. The Doors were fired from the Whisky on August 21, 1966, when Morrison added an explicit retelling and profanity-laden version of the Greek myth of Oedipus during "The End".[28]

The Doors and Foreign Days (August 1966 – December 1967) [edit]

The Doors recorded their self-titled debut anthology betwixt August and September 1966, at Sunset Audio Recording Studios. The record was officially released in the start week of January 1967. It included many pop songs from their repertory, among those, the nearly 12-minute musical drama "The Cease". In November 1966, Mark Abramson directed a promotional motion picture for the lead unmarried "Interruption On Through (To the Other Side)". The group also made several television appearances, such every bit on Shebang, a Los Angeles television show, miming to a playback of "Interruption On Through".[nb 4] In early 1967, the group appeared on The Clay Cole Show (which aired on Saturday evenings at 6 pm on WPIX Channel 11 out of New York Metropolis) where they performed their single "Break On Through". Since the single acquired only minor success, the band turned to "Calorie-free My Fire"; it became the kickoff single from Elektra Records to reach number one on the Billboard Hot 100 singles nautical chart, selling over ane million copies.[31]

From March 7 to 11, 1967, the Doors performed at the Matrix Club in San Francisco, California. The March vii and 10 shows were recorded past a co-owner of the Matrix, Peter Abram. These recordings are notable as they are among the earliest alive recordings of the band to circulate. On November 18, 2008, the Doors published a compilation of these recordings, Alive at the Matrix 1967, on the ring's boutique Vivid Midnight Archives label.[32] [33]

The Doors made their international television debut in May 1967, performing a version of "The End" for the Canadian Dissemination Corporation (CBC) at O'Keefe Eye in Toronto.[34] Simply after its initial broadcasts, the performance remained unreleased except in homemade form until the release of The Doors Soundstage Performances DVD in 2002.[34] On August 25, 1967, they appeared on American television, guest-starring on the variety Television set series Malibu U, performing "Light My Fire", though they did not announced live. The band is seen on a beach and is lipsynching the song in playback. The music video did not gain any commercial success and the operation fell into relative obscurity.[35] Information technology was not until they appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show that they gained attention on television.[36]

On September 17, 1967, the Doors gave a memorable performance of "Light My Fire" on The Ed Sullivan Show.[36] According to Manzarek, network executives asked that the word "college" exist removed, due to a possible reference to drug use.[37] The group appeared to acquiesce, merely performed the vocal in its original form, because either they had never intended to comply with the request or Jim Morrison was nervous and forgot to make the change (the group has given conflicting accounts).[38] Either style, "higher" was sung out on national television, and the show's host, Ed Sullivan, canceled another half dozen shows that had been planned. Later on the program's producer told the band they volition never perform on the show again,[37] Morrison reportedly replied: "Hey man. We just did the Sullivan Show."[36] [39]

On Dec 24, the Doors performed "Light My Fire" and "Moonlight Bulldoze" live for The Jonathan Winters Show. Their performance was taped for later on broadcast. From December 26 to 28, the grouping played at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco; during ane prepare the band stopped performing to watch themselves on The Jonathan Winters Testify on a television set set up wheeled onto the stage.[40]

The Doors spent several weeks in Sunset Studios in Los Angeles recording their second album, Foreign Days, experimenting with the new technology, notably the Moog synthesizer they at present had available.[41] The commercial success of Strange Days was middling, peaking at number three on the Billboard album nautical chart only rapidly dropping, along with a series of underperforming singles.[31] The chorus from the anthology'due south single "People Are Strange" inspired the name of the 2009 documentary of the Doors, When You're Strange.[21]

Although session musician Larry Knechtel had occasionally contributed bass on the band's debut album,[42] Strange Days was the first Doors anthology recorded with a studio musician, playing bass on the majority of the record, and this continued on all subsequent studio albums.[43] Manzarek explained that his keyboard bass was well-suited for alive situations but that it lacked the "articulation" needed for studio recording.[43] Douglass Lubahn played on Strange Days and the adjacent ii albums; but the band used several other musicians for this part, often using more than than i bassist on the aforementioned album. Kerry Magness, Leroy Vinnegar, Harvey Brooks, Ray Neopolitan, Lonnie Mack, Jerry Scheff, Jack Conrad (who played a major role in the post Morrison years touring with the group in 1971 and 1972), Chris Ethridge, Charles Larkey and Leland Sklar are credited as bassists who worked with the band.[44]

New Haven incident (Dec 1967) [edit]

On December nine, 1967, the Doors performed a now-infamous concert at New Haven Arena in New Haven, Connecticut, which concluded abruptly when Morrison was arrested by local police.[45] Morrison became the outset rock artist to exist arrested onstage during a concert performance.[46] [47] Morrison had been kissing a female fan backstage in a bath shower stall prior to the first of the concert when a police officer happened upon them. Unaware that he was the pb vocalist of the band virtually to perform, the officeholder told Morrison and the fan to go out, to which Morrison said, "Eat it." The policeman took out a can of mace and warned Morrison, "Final chance", to which Morrison replied, "Last adventure to consume it."[48] [49] There is some discrepancy every bit to what happened next: according to No One Here Gets Out Live, the fan ran away and Morrison was maced; but Manzarek recounts in his book that both Morrison and the fan were sprayed.[48] [50] [51]

The Doors' main human action was delayed for an hr while Morrison recovered, after which the band took the stage very late. According to an authenticated fan account that Krieger posted to his Facebook page, the law nonetheless did not consider the event resolved, and wanted to charge him. Halfway through the first gear up, Morrison proceeded to create an improvised song (every bit depicted in the Oliver Rock movie) about his feel with the "lilliputian men in blue". It was an obscenity-laced business relationship to the audience, describing what had happened backstage and taunting the police, who were surrounding the phase.[52] The concert was surlily ended when Morrison was dragged offstage by the police. The audience, which was already restless from waiting so long for the band to perform, became unruly. Morrison was taken to a local constabulary station, photographed and booked on charges of inciting a riot, indecency and public obscenity. Charges confronting Morrison, besides as those against three journalists also arrested in the incident (Mike Zwerin, Yvonne Chabrier and Tim Page), were dropped several weeks later for lack of evidence.[47] [50]

Waiting for the Dominicus (April–December 1968) [edit]

Recording of the grouping's third album in April 1968 was marred past tension as a result of Morrison'south increasing dependence on alcohol and the rejection of the 17-minute "Celebration of the Lizard" by band producer Paul Rothchild, who considered the piece of work not commercial enough.[53] Approaching the height of their popularity, the Doors played a series of outdoor shows that led to frenzied scenes between fans and law, specially at Chicago Coliseum on May x.[54]

The band began to branch out from their initial course for this third LP, and began writing new material. Waiting for the Sunday became their offset and only album to achieve Number 1 on the United states of america charts, and the unmarried "Hi, I Beloved You" (one of the vi songs performed by the band on their 1965 Aura Records demo) was their second US No. ane single. Following the 1968 release of "Howdy, I Beloved Yous", the publisher of the Kinks' 1964 hit "All Day and All of the Nighttime" announced they were planning legal action against the Doors for copyright infringement; notwithstanding, songwriter Ray Davies ultimately chose not to sue.[55] [nb 5] Kinks guitarist Dave Davies was particularly irritated past the similarity.[57] In concert, Morrison was occasionally dismissive of the song, leaving the vocals to Manzarek, as can be seen in the documentary The Doors Are Open.[58]

A month after a riotous concert at the Singer Bowl in New York City, the group flew to Swell Great britain for their first operation outside North America. They held a press briefing at the ICA Gallery in London and played shows at the Roundhouse. The results of the trip were broadcast on Granada Television'south The Doors Are Open, later on released on video. They played dates in Europe, along with Jefferson Airplane, including a show in Amsterdam where Morrison collapsed on phase later a drug binge (including marijuana, hashish and unspecified pills).[59]

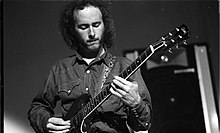

Robby Krieger at Roundhouse in London (September 1968).

The grouping flew dorsum to the United States and played nine more dates earlier returning to work in November on their fourth LP. They ended the year with a successful new single, "Touch Me" (released in Dec 1968), which reached No. iii on the Billboard Hot 100 and No. one in the Cashbox Acme 100 in early on 1969; this was the group's third and last American number-1 single.[lx]

Miami incident (March 1969) [edit]

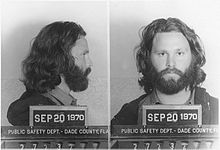

Jim Morrison on the day of his conviction in Miami for profanity and indecent exposure

On March 1, 1969, at the Dinner Key Auditorium in the Kokosnoot Grove neighborhood of Miami, the Doors gave the about controversial performance of their career, ane that nearly "derailed the band".[seven] The auditorium was a converted seaplane hangar that had no ac on that hot night, and the seats had been removed by the promoter to boost ticket sales.[61] [62]

Morrison had been drinking all day and had missed connecting flights to Miami. By the time he arrived, drunk, the concert was over an hr late.[61] [63] The restless crowd of 12,000, packed into a facility designed to hold 7,000, was subjected to undue silences in Morrison'south singing, which strained the music from the beginning of the performance. Morrison had recently attended a play by an experimental theater group the Living Theatre and was inspired by their "antagonistic" style of performance fine art.[64] [65] Morrison taunted the crowd with messages of both love and hate, saying, "Love me. I can't accept information technology no more without no skillful love. I desire some lovin'. Ain't nobody gonna beloved my donkey?" and alternately, "You're all a bunch of fuckin' idiots!" and screaming "What are you gonna exercise nearly it?" over and over again.[65] [66] [63]

As the band began their second song, "Touch Me", Morrison started shouting in protest, forcing the band to a halt. At one point, Morrison removed the hat of an onstage police officer and threw it into the crowd; the officer removed Morrison's hat and threw it.[67] Manager Beak Siddons recalled, "The gig was a baroque, circus-like thing, at that place was this guy conveying a sheep and the wildest people that I'd ever seen."[68] Equipment chief Vince Treanor said, "Somebody jumped up and poured champagne on Jim so he took his shirt off, he was soaking wet. 'Permit'south encounter a little skin, let's go naked,' he said, and the audience started taking their clothes off."[68] Having removed his shirt, Morrison held it in forepart of his groin area and started to make hand movements behind it.[69] Manzarek described the incident as a mass "religious hallucination".[69]

On March five, the Dade County Sheriff'southward office issued a warrant for Morrison's arrest, claiming Morrison had exposed his penis while on stage, shouted obscenities to the oversupply, simulated oral sex on Krieger, and was drunk at the time of his performance. Morrison turned down a plea bargain that required the Doors to perform a costless Miami concert. He was bedevilled and sentenced to 6 months in jail with hard labor, and ordered to pay a $500 fine.[seventy] [71] Morrison remained costless, pending an appeal of his conviction, and died before the matter was legally resolved. In 2007 Florida Governor Charlie Crist suggested the possibility of a posthumous pardon for Morrison, which was announced as successful on December 9, 2010.[72] Densmore, Krieger and Manzarek have denied the allegation that Morrison exposed himself on stage that nighttime.[73] [74] [75]

The Soft Parade (May–July 1969) [edit]

The Doors' fourth album, The Soft Parade, released in July 1969, was their first-and-simply to characteristic brass and string arrangements. The concept was suggested by Rothchild to the ring, later on listening many examples past various groups who besides explored the same radical departure.[76] Densmore and Manzarek (who both were influenced by jazz music) agreed with the recommendation,[77] only Morrison declined to contain orchestral accessory on his compositions.[78] The lead single, "Affect Me", featured saxophonist Curtis Amy.[79]

While the band was trying to maintain their previous momentum, efforts to expand their sound gave the anthology an experimental experience, causing critics to attack their musical integrity.[80] According to Densmore in his biography Riders on the Storm, private writing credits were noted for the get-go time because of Morrison'southward reluctance to sing the lyrics of Krieger's song "Tell All the People". Morrison's drinking made him difficult and unreliable, and the recording sessions dragged on for months. Studio costs piled up, and the Doors came close to disintegrating. Despite all this, the album was immensely successful, becoming the band'south fourth hit anthology.[81]

Morrison Hotel and Absolutely Live (November 1969 – December 1970) [edit]

During the recording of their adjacent anthology, Morrison Hotel, in November 1969, Morrison again found himself in trouble with the law afterwards harassing airline staff during a flight to Phoenix, Arizona to see the Rolling Stones in concert. Both Morrison and his friend and traveling companion Tom Baker were charged with "interfering with the flight of an intercontinental aircraft and public drunkenness".[82] If convicted of the most serious charge, Morrison could have faced a ten-twelvemonth federal prison sentence for the incident.[83] The charges were dropped in April 1970 after an airline stewardess reversed her testimony to say she mistakenly identified Morrison equally Baker.[84]

The Doors staged a render to a more conventional direction after the experimental The Soft Parade, with their 1970 LP Morrison Hotel, their fifth anthology. Featuring a consequent blues rock sound, the anthology's opener was "Roadhouse Dejection". The record reached No. iv in the United States and revived their status among their core fanbase and the rock press. Dave Marsh, the editor of Creem magazine, said of the album: "the most horrifying rock and roll I have e'er heard. When they're adept, they're just unbeatable. I know this is the all-time record I've listened to ... and so far".[83] Rock Magazine called information technology "without any incertitude their ballsiest (and best) anthology to appointment".[83] Circus magazine praised it as "possibly the best anthology all the same from the Doors" and "good hard, evil rock, and one of the all-time albums released this decade".[83] The album also saw Morrison returning every bit main songwriter, writing or co-writing all of the album's tracks. The 40th anniversary CD reissue of Morrison Hotel contains outtakes and alternative takes, including different versions of "The Spy" and "Roadhouse Blues" (with Lonnie Mack on bass guitar and the Lovin' Spoonful's John Sebastian on harmonica).

July 1970 saw the release of the group's first live album, Absolutely Live, which peaked at No. 8 position.[85] The record was completed by producer Rothchild, who confirmed that the anthology's last mixing consisted of many bits and pieces from various and different band concerts. "There must be 2000 edits on that album," he told an interviewer years afterward.[76] Absolutely Live also includes the beginning release of the lengthy piece "Celebration of the Lizard".

Although the Doors continued to face de facto bans in more conservative American markets and earned new bans at Salt Lake City's Salt Palace and Detroit's Cobo Hall following tumultuous concerts,[86] [87] the ring managed to play xviii concerts in the Usa, Mexico and Canada following the Miami incident in 1969,[88] and 23 dates in the United States and Canada throughout the outset half of 1970. The grouping afterward fabricated information technology to the Island of Wight Festival on August 29; performing on the same twenty-four hour period as John Sebastian, Shawn Phillips, Lighthouse, Joni Mitchell, Tiny Tim, Miles Davis, 10 Years Subsequently, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, the Who, Sly and the Family Stone and Melanie;[89] the functioning was the final captured in the band's Roadhouse Dejection Tour.[xc]

On December 8, 1970, his 27th birthday, Morrison recorded another poetry session. Office of this would end upward on An American Prayer in 1978 with music, and is currently in the possession of the Courson family.[91] Shortly thereafter, a new bout to promote their upcoming album would incorporate merely three dates.[92] 2 concerts were held in Dallas on December xi. During the Doors' last public functioning with Morrison, at The Warehouse in New Orleans, on December 12, 1970, Morrison patently had a breakdown on stage. Midway through the set he slammed the microphone numerous times into the stage floor until the platform below was destroyed, then sat down and refused to perform for the rest of the testify.[93] Afterward the show, Densmore met with Manzarek and Krieger; they decided to cease their alive act, citing their mutual understanding that Morrison was ready to retire from performing.[94]

50.A. Woman and Morrison'southward expiry (December 1970 – July 1971) [edit]

Despite Morrison'south confidence and the fallout from their advent in New Orleans, the Doors set out to reclaim their status as a premier act with L.A. Woman in 1971.[95] The anthology included rhythm guitarist Marc Benno on several tracks and prominently featured bassist Jerry Scheff, best known for his work in Elvis Presley's TCB Band. Despite a comparatively depression Billboard chart peak at No. 9, 50.A. Adult female contained ii Summit 20 hits and went on to be their second acknowledged studio anthology, surpassed in sales just by their debut.[96] The album explored their R&B roots,[97] although during rehearsals they had a falling-out with Paul Rothchild, who was dissatisfied with the band's effort. Denouncing "Love Her Madly" as "cocktail lounge music", he quit and handed the production to Bruce Botnick and the Doors.[76]

The championship track and two singles ("Love Her Madly" and "Riders on the Storm") remain mainstays of rock radio programming,[98] with the latter being inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame for its special significance to recorded music. In the song "Fifty.A. Woman", Morrison makes an anagram of his name to dirge "Mr. Mojo Risin".[99] During the sessions, a short clip of the band performing "Crawling King Snake" was filmed. Equally far as is known, this is the last clip of the Doors performing with Morrison.

On March xiii, 1971, following the recording of L.A. Woman, Morrison took a leave of absence from the Doors and moved to Paris with Pamela Courson; he had reportedly visited the city the previous summertime. On July 3, 1971, following months of settling, Morrison was constitute expressionless in the bath by Courson.[100] Despite the absence of an official autopsy, the reason of expiry was listed every bit heart failure.[101] Morrison was buried in the "Poets' Corner" of Père Lachaise Cemetery on July vii.[102] [103]

Morrison died at age 27, the same age as several other famous rock stars in the 27 Club. In 1974, Morrison's girlfriend Pamela Courson too died at the age of 27.[104]

After Morrison [edit]

Other Voices and Full Circle (July 1971 – January 1973) [edit]

Densmore, Krieger and Manzarek in 1971

Morrison's passing stamped the Doors with a seal of legend and immortality. In that location was no opportunity for the ring to go into the seventies intact. Perhaps that's a good thing. I can't imagine the Doors in the era of disco.

L.A. Woman 's follow up album, Other Voices, was being planned while Morrison was in Paris. The band assumed he would return to help them complete the album.[106] After Morrison died, the surviving members considered replacing him with several new people, such every bit Paul McCartney on bass,[107] and Iggy Pop on vocals.[108] But after neither of these worked out, Krieger and Manzarek took over lead song duties themselves.[106] Other Voices was finally completed in August 1971, and released in Oct 1971. The tape featured the single "Tightrope Ride", which received some radio airplay. The trio began performing again with additional supporting members on November 12, 1971, at Pershing Municipal Auditorium in Lincoln, Nebraska, followed by shows at Carnegie Hall in November 23, and the Hollywood Palladium in November 26.[106]

The recordings for Full Circumvolve took identify a year afterwards Other Voices during the bound of 1972, and the album was released in August 1972. For the tours during this period, the Doors enlisted Jack Conrad on bass (who had played on several tracks on both Other Voices and Full Circle) likewise as Bobby Ray Henson on rhythm guitar. They began a European tour covering France, Germany, holland, and the United kingdom, including an appearance on the German evidence Beat-Club. Like Other Voices, Total Circle did not perform as well commercially as their previous albums. While Total Circle was notable for adding elements of funk and jazz to the classic Doors audio,[109] the ring struggled with Manzarek and Krieger leading (neither of the mail-Morrison albums had reached the Meridian x while all half-dozen of their albums with Morrison had).[110] Once their contract with Elektra had elapsed the Doors disbanded in 1973.[7]

Reunions [edit]

The tertiary postal service-Morrison album, An American Prayer, was released in 1978. It consisted of the ring adding musical backing tracks to previously recorded spoken word performances of Morrison reciting his poetry. The record was a commercial success, acquiring a platinum certificate.[111] Ii years later, information technology was nominated for a Grammy Award in the "Spoken Word Album" category, merely it had ultimately lost to John Gielgud's The Ages of Homo.[112] An American Prayer was re-mastered and re-released with bonus tracks in 1995.[113]

In 1993, the Doors were inducted into the Stone and Ringlet Hall of Fame.[114] For the ceremony Manzarek, Krieger and Densmore reunited again to perform "Roadhouse Dejection", "Break On Through" and "Lite My Fire". Eddie Vedder filled in on atomic number 82 vocals, while Don Was played bass.[115] For the 1997 boxed set, the surviving members of the Doors once again reunited to complete "Orange Canton Suite". The rail was one that Morrison had written and recorded, providing vocals and piano.

The Doors reunited in 2000 to perform on VH1's Storytellers. For the live performance, the band was joined by Angelo Barbera and numerous guest vocalists, including Ian Astbury (of the Cult), Scott Weiland, Scott Stapp, Perry Farrell, Pat Monahan and Travis Meeks. Following the recording the Storytellers: A Celebration, the ring members joined to record music for the Stoned Immaculate: The Music of The Doors tribute anthology.[116] On May 29, 2007, Perry Farrell's group the Satellite Party released its offset album Ultra Payloaded on Columbia Records. The album features "Adult female in the Window", a new song with music and a pre-recorded vocal performance provided by Morrison.

"I like to say this is the first new Doors rail of the 21st century", Manzarek said of a new song he recorded with Krieger, Densmore and DJ/producer Skrillex (Sonny Moore). The recording session and vocal are part of a documentary motion picture, Re:GENERATION, that recruited five popular DJs/producers to work with artists from five carve up genres and had them record new music. Manzarek and Skrillex had an firsthand musical connectedness. "Sonny plays his beat, all he had to exercise was play the ane thing. I listened to it and I said, 'Holy shit, that's strong,'" Manzarek says. "Basically, information technology's a variation on 'Milestones', past Miles Davis, and if I practice say so myself, sounds fucking groovy, hot every bit hell."[117] The track, called "Breakn' a Sweat", was included on Skrillex'south EP Bangarang.[118]

In 2013, the remaining members of the Doors recorded with rapper Tech N9ne for the song "Strange 2013", appearing on his album Something Else, which features new instrumentation by the band and samples of Morrison'southward vocals from the song "Strange Days".[119] In their final collaboration before Manzarek's death, the three surviving Doors provided backing for poet Michael C. Ford's album Expect Each Other in The Ears.

On February 12, 2016, at The Fonda Theatre in Hollywood, Densmore and Krieger reunited for the starting time fourth dimension in 15 years to perform in tribute to Manzarek and benefit Stand Upwards to Cancer. That day would take been Manzarek's 77th altogether.[120] The night featured Exene Cervenka and John Doe of the band X, Rami Jaffee of the Foo Fighters, Rock Temple Pilots' Robert Deleo, Jane's Addiction's Stephen Perkins, Emily Armstrong of Expressionless Sara, Andrew Watt, amidst others.[121]

Afterward the Doors [edit]

After Morrison died in 1971, Krieger and Densmore formed the Butts Ring as a consequence of trying to find a new lead singer to supervene upon Morrison.[122] The surviving Doors members went to London looking for a new lead singer. They formed the Butts Band in 1973 there, signing with Blue Pollex records. They released an album titled Butts Band the same year, so disbanded in 1975 after a second album with Phil Chen on bass.[123]

Manzarek fabricated 3 solo albums from 1974 to 1983 and formed a ring called Nite City in 1975, which released two albums in 1977–1978, while Krieger released six solo albums from 1977 to 2010.[124]

In 2002, Manzarek and Krieger formed together a new version of the Doors which they called the Doors of the 21st Century. After legal battles with Densmore over utilise of the Doors proper name, they changed their proper noun several times and ultimately toured under the proper noun "Manzarek–Krieger" or "Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger of the Doors". The grouping toured extensively throughout their career.[125] In July 2007, Densmore said he would not reunite with the Doors unless Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam was the lead singer.[126]

On May 20, 2013, Manzarek died at a hospital in Rosenheim, Germany, at the age of 74 due to complications related to bile duct cancer.[127] Krieger and Densmore came together on Feb 12, 2016, at a benefit concert memorial for Manzarek. All gain went to "Stand up Up to Cancer".[128]

Legacy [edit]

Kickoff in the tardily 1970s, there was a sustained revival of involvement in the Doors which created a new generation of fans.[129] The origin of the revival is traced to the release of the album An American Prayer in late 1978 which contained a alive version of "Roadhouse Blues" that received considerable airplay on album-oriented rock radio stations. In 1979 the song "The End" was featured in dramatic fashion in the movie Apocalypse Now,[vii] [130] and the next year the acknowledged biography of Morrison, No One Here Gets Out Alive, was published. The Doors' offset album, The Doors, re-entered the Billboard 200 album chart in September 1980 and Elektra Records reported the Doors' albums were selling better than in any twelvemonth since their original release.[131] In September 1981, Rolling Stone ran a cover story on Morrison and the band, with the title "Jim Morrison: He'due south Hot, He's Sexy and He's Expressionless."[131] In response a new compilation album, Greatest Hits, was released in October 1980. The album peaked at No. 17 in Billboard and remained on the chart for virtually 2 years.[132]

The revival continued in 1983 with the release of Alive, She Cried, an anthology of previously unreleased live recordings. The rail "Gloria" reached No. xviii on the Billboard Summit Tracks chart[133] and the video was in heavy rotation on MTV.[134] Some other compilation album, The All-time of the Doors was released in 1987 and went on to be certified Diamond in 2007 by the Recording Industry Association of America for sales of x million certified units.[135]

A second revival, attracting another generation of fans, occurred in 1991 following the release of the film The Doors, directed by Oliver Stone and starring Val Kilmer as Morrison. Stone created the script from over a hundred interviews of people who were in Morrison's life.[136] He designed the movie by picking the songs and so adding the appropriate scripts to them.[137] The original band members did not like the moving-picture show's portrayal of the events. In the book The Doors, Manzarek states, "That Oliver Stone thing did existent damage to the guy I knew: Jim Morrison, the poet." In addition, Manzarek claims that he wanted the movie to exist about all iv members of the band, not only Morrison.[138] Densmore said, "A third of it's fiction."[139] In the same volume, Krieger agrees with the other ii, but also says, "It could have been a lot worse." The picture show's soundtrack album reached No. 8 on the Billboard anthology nautical chart and Greatest Hits and The All-time of the Doors re-entered the chart, with the latter reaching a new peak position of No. 32.

Awards and critical accolades:

- In 1993, the Doors were inducted into the Stone and Curlicue Hall of Fame.[140]

- In 1998, "Light My Fire" was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame under the category Rock (track).[141]

- In 1998, VH-1 compiled a listing of the 100 Greatest Artists of Rock and Curlicue. The Doors were ranked number xx by top music artists while Rock on the Cyberspace readers ranked them number fifteen.[142]

- In 2000, the Doors were ranked number 32 on VH1's 100 Greatest Difficult Stone Artists,[143] and "Low-cal My Fire" was ranked number seven on VH1's Greatest Rock Songs.[144]

- In 2002, their self-titled anthology' was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame under the category Rock (Album).[141]

- In 2004, Rolling Stone ranked the Doors 41st on their list of 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[13]

- Also in 2004, Rolling Rock magazine's list of The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time included ii of their songs: "Low-cal My Fire" at number 35 and "The End" at number 328.[145]

- In 2007, the Doors received a Grammy Award for lifetime achievement.[146]

- In 2007, the Doors received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[147]

- In 2010, "Riders on the Storm" was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame under the category Rock (track).[141]

- In 2011, the Doors received a Grammy Award in Best Long Form Music Video for the film When Yous're Strange, directed by Tom DiCillo.[148]

- In 2012, Rolling Stone magazine's list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Fourth dimension included three of their studio albums; the self-titled anthology at number 42, L.A. Woman at number 362, and Foreign Days at number 407.[149]

- In 2014, the Doors were voted by British Archetype Rock mag'due south readers to receive that year's Roll of Honour Tommy Vance "Inspiration" Accolade.[150]

- In 2015, the Library of Congress selected The Doors for inclusion in the National Recording Registry based on its cultural, creative or historical significance.[151]

- In 2016, the Doors received a Grammy Award in Favorite Reissues and Compilation for the live anthology London Fog 1966.[152]

- The Doors were honored for the 50th ceremony of their self-titled album release, Jan iv, 2017, with the city of Los Angeles proclaiming that engagement "The Day of the Doors".[153] At a ceremony in Venice, Los Angeles Councilmember Mike Bonin introduced surviving members Densmore and Krieger, presenting them with a framed announcement and lighting a Doors sign beneath the famed 'Venice' letters.[154]

- The 2018 Asbury Park Music & Film Festival has announced the picture show submission honour winners. The anniversary was held on Sunday, April 29 at the Asbury Hotel hosted by Shelli Sonstein, two-time Gracie Award winner, co-host of the Jim Kerr Stone and Curl Morning Show on Q104.3 and APMFF Board member. The film Break on Thru: Commemoration of Ray Manzarek and The Doors, won the best length feature at the festival.[155]

- In 2020, Rolling Stone listed the 50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition of Morrison Hotel among "The Best Box Sets of the Year".[156]

Band members [edit]

- Jim Morrison – lead vocals, harmonica, percussion (1965–1971; died 1971)

- Ray Manzarek – keyboards, keyboard bass, bankroll and lead vocals (1965–1973, 1978; 2012; died 2013)

- Robby Krieger – electric guitar, bankroll and pb vocals (1965–1973, 1978, 2012)

- John Densmore – drums, percussion, backing vocals (1965–1973, 1978, 2012)

Discography [edit]

- The Doors (1967)

- Strange Days (1967)

- Waiting for the Sun (1968)

- The Soft Parade (1969)

- Morrison Hotel (1970)

- L.A. Adult female (1971)

- Other Voices (1971)

- Full Circle (1972)

- An American Prayer (1978)

Videography [edit]

- The Doors Are Open (1968)

- A Tribute to Jim Morrison (1981)

- Dance on Burn down (1985)

- Live at the Hollywood Bowl (1987)

- Live in Europe 1968 (1989)

- The Doors (1991)

- The Soft Parade a Retrospective (1991)

- The All-time of the Doors (1997)

- The Doors Collection – Collector's Edition (1999)

- VH1 Storytellers – The Doors: A Celebration (2001)

- The Doors – 30 Years Commemorative Edition (2001)

- No One Here Gets Out Live (2001)

- Soundstage Performances (2002)

- The Doors of the 21st Century: Fifty.A. Adult female Alive (2003)

- The Doors Collector'southward Edition – (3 DVD) (2005)

- Classic Albums: The Doors (2008)

- When You're Strange (2009)

- Mr. Mojo Risin' : The Story of L.A. Adult female (2011)

- Live at the Bowl '68 (2012)

- R-Evolution (2013)

- The Doors Special Edition – (3 DVD) (2013)

- Feast of Friends (2014)

- Alive at the Isle of Wight Festival 1970 (2018)

- Pause on Thru: Commemoration of Ray Manzarek and The Doors (2018)

Notes [edit]

- ^ In the official DVD Dance on Burn down features in the credits of the song "Riders on the Storm": "They would become the offset American band to accumulate eight consecutive gold and platinum LPs."[9]

- ^ Patty Sullivan was afterward credited using her married name Patricia Hansen in the Doors' 1997 Box Prepare CD release.[19] [xx]

- ^ This recordings were officially available much later in Oct 1997, on the Doors' Box Gear up CD release. This has circulated widely since then every bit a bootleg recording.[20]

- ^ According to The Doors FAQ author Richie Weidman, this was either New Yr'due south Day 1967,[29] or March 6, 1967, as noted by Gillian G. Gaar.[xxx]

- ^ Nevertheless, some take supported that the court in the United Kingdom determined in favor of Davies and any royalties for the vocal are paid to him.[56]

References [edit]

- ^ Debolt & Baugess 2011, pp. 544–.

- ^ Wallace 2010, pp. 68–.

- ^ Einarson 2001, p. 8.

- ^ Weil, Martin (May 20, 2013). "Ray Manzarek, Keyboardist and Founding Member of the Doors, Dies at 74". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on Dec 16, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. May 31, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "'Doors Sold 4,190,457 Albums': Court Report". Billboard. December 18, 1971. p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Ruhlmann, William; Unterberger, Richie. "The Doors – Biography". AllMusic . Retrieved Jan 1, 2010.

- ^ "The Doors Biography". Rolling Stone. March xvi, 2012. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved August xvi, 2016.

- ^ Dance on Fire. Event occurs at 64:26. Retrieved February 20, 2019 – via Yandex.

- ^ "Top Selling Artists". RIAA . Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ Kelsey, Eric (May 20, 2013). "Keyboardist Ray Manzarek of The Doors dies at age 74". Reuters . Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Quan, Denise (June 25, 2013). "The Doors plan tribute concert for Ray Manzarek". CNN. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Manson, Marilyn (April 15, 2004). "The Immortals – The Greatest Artists of All Time: No. 41 The Doors". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 21, 2006.

- ^ Manzarek 1998, p. 94.

- ^ Davis 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Rogers, Brent. "NPR interview with Ray Manzarek". NPR – Publicly accessed. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 43.

- ^ The Doors (July 10, 2012). The Grove Dictionary of American Music (2nd ed.).

- ^ Weidman 2011, p. 88.

- ^ a b The Doors: Box Gear up (Liner notes). The Doors. Elektra Records. 1997. 62123-2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b The Doors (2010). When Y'all're Foreign (Documentary). Rhino Entertainment.

- ^ Densmore 1990, p. 53.

- ^ Manzarek 1998, p. 139.

- ^ a b c Weidman 2011, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Goldstein, Patrick (September 1977). "Nite City: The Dark Side of 50.A." Creem. Archived from the original on July ix, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Weidman 2011, p. 128.

- ^ Gaar 2015, p. 26. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGaar2015 (help)

- ^ Cherry 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Weidman 2011, p. 251.

- ^ Gaar 2015, p. 41. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGaar2015 (assistance)

- ^ a b Brodsky, Joel (February 2004). "Psychotic Reaction". Mojo.

- ^ Simpson, Dave (December 19, 2008). "Movie & Music: Rock & Pop: The CDs We Missed: The Doors: Live at the Matrix 1967: 4 Stars: (Rhino)". The Guardian.

- ^ Selvin, Joel (November 17, 2018). "City'southward Psychedelic Past Dorsum In View In Doors' Matrix Discs". San Francisco Relate.

- ^ a b The Doors (2002). The Doors Soundstage Performances (DVD). Toronto, Copenhagen, New York: Hawkeye Vision.

- ^ The Doors. The Doors – Light My Burn down (1967) Malibu U TV. Dailymotion.com . Retrieved Oct 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Doors Ed Sullivan". The Ed Sullivan Evidence. (SOFA Amusement). Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ a b Manzarek 1998, p. 253.

- ^ Whitaker, Sterling (September 17, 2015). "When the Doors Got Banned from The Ed Sullivan Prove". Ultimate Classic Rock . Retrieved December three, 2021.

- ^ Hogan 1994, p. 30.

- ^ Davis 2005, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Davis 2005, p. 197.

- ^ Fong-Torres 2006, p. 71.

- ^ a b Manzarek 1998, p. 258.

- ^ These credits are included in AllMusic overviews of the group's half dozen studio albums released during Morrison's lifetime; these sources are every bit follows:

- "Strange Days – Credits". AllMusic . Retrieved Baronial 31, 2020.

- "Waiting for the Lord's day – Credits". AllMusic . Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "The Soft Parade – Credits". AllMusic . Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "Morrison Hotel – Credits". AllMusic . Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "L.A. Woman – Credits". AllMusic . Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "New Haven Police Close 'The Doors'; Use of Mace Reported". The New York Times. December 10, 1967. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- ^ Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, p. xx.

- ^ a b Davis 2005, p. 216.

- ^ a b Hopkins & Sugerman 1980, p. 160.

- ^ Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, p. 202.

- ^ a b Manzarek 1998, p. 272.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "Jim Morrison – Biography". AllMusic . Retrieved January one, 2009.

- ^ Whitaker, Sterling (Dec 9, 2015). "Why Jim Morrison Got Arrested Onstage in New Haven". Ultimate Classic Rock . Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Wall 2014, p. 197.

- ^ Weidman 2011, p. 268.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Deevoy, Adrian (May 11, 2017). "The Kinks' Ray Davies: Brexit is 'Bigger Than the Berlin Wall'". The Guardian . Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Loyal Pains: The Davies Boys Are Notwithstanding at It". Archived from the original on September vii, 2006. Retrieved December 23, 2006.

- ^ The Doors (1968). The Doors are Open (Concert/Documentary). The Roadhouse, London.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael (September 15, 2015). "When Ray Manzarek Had to Fill up in for a Passed-Out Jim Morrison". Ultimate Classic Stone . Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "Once Upon a Time in the Top Spot: The Doors, 'Touch Me'". Rhinoceros.com. Feb 12, 2019. Retrieved Apr 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Hopkins & Sugerman 1980, p. 227.

- ^ Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, p. 293.

- ^ a b Manzarek 1998, p. 312.

- ^ Manzarek 1998, p. 310.

- ^ a b Riordan & Prochnicky, pp. 292–293, 295. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRiordanProchnicky (assist)

- ^ Hopkins & Sugerman 1980, p. 230.

- ^ Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, p. 296.

- ^ a b Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, p. 297.

- ^ a b "BBC Radio ii – Mr Mojo Risin'". BBC. June 29, 2011.

- ^ "Mar v, 1969: Jim Morrison is charged with lewd behavior at a Miami concert". History.com . Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ^ "2007 Alphabetic character to Governor Crist". Doors.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved Baronial twenty, 2011.

- ^ "Florida pardons Doors' Jim Morrison". Reuters. December nine, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Drummer says Jim Morrison never exposed himself". Reuters. December 2, 2010. Retrieved Dec 9, 2010.

- ^ Manzarek 1998, p. 314.

- ^ Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, p. 299.

- ^ a b c Jackson, Blair (July 3, 1981). BAM Interview with Paul Rothchild. Vol. 107 – via Waiting for the Sunday Archives.

- ^ Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, p. 320.

- ^ Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, pp. 338–340.

- ^ Ursula Dawn Goldsmith 2019, p. 94.

- ^ Matijas-Mecca 2020, p. 80.

- ^ Densmore 1990, p. 187.

- ^ Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, p. 347.

- ^ a b c d Hopkins & Sugerman 1980, p. 284.

- ^ Hopkins & Sugerman 1980, p. 290.

- ^ Gaar 2015, p. 102. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGaar2015 (help)

- ^ Lifton, Dave (May 9, 2015). "How the Doors Got Banned from Detroit's Cobo Arena". Ultimate Classic Rock . Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "The Doors Cancelled Performances | Salt Lake City 1970". Mildequator.com . Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "The Doors Concert Dates & Info 1969". Mildequator.com . Retrieved Jan 15, 2020.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Island of Wight Festival". AllMusic . Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "The Doors Concert Dates & Info 1970". Mildequator.com . Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ Weidman 2011, p. 375.

- ^ "The Doors: An American Prayer". Rhino.com. November 27, 2018. Retrieved Feb 11, 2021.

- ^ Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, pp. 438–439.

- ^ Hopkins & Sugerman 1980, p. 309.

- ^ Runtagh, Hashemite kingdom of jordan (April 19, 2016). "Doors' L.A. Woman: 10 Things You lot Didn't Know". Rolling Stone . Retrieved March sixteen, 2021.

- ^ Ursula Dawn Goldsmith 2019, p. 92.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael (February one, 2016). "When the Doors Went Dorsum to Basics on Morrison Hotel". Ultimate Archetype Rock . Retrieved May 29, 2021.

In the end, it turned out to be a smart move for the band, which returned to the studio at the stop of the year to make its last album with Morrison, L.A. Woman, a recharged take on the R&B and dejection roots music it returned to on Morrison Hotel.

- ^ Hochman, Steve (Baronial 3, 2003). "21st Century Doors Make Grave Decision". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved Jan 15, 2020.

- ^ Whitman, Howard. "Blu-ray Motion-picture show Review: Doors – Mr. Mojo Risin': The Story of L.A. Woman". Technologytell.com.

- ^ Fong-Torres, Ben (August 5, 1971). "James Douglas Morrison, Poet: Dead at 27". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on Feb 22, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Giles, Jeff (July 3, 2015). "The Mean solar day Jim Morrison's Body Was Discovered". Ultimate Classic Stone . Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ Davis 2005, p. 472.

- ^ Olsen 2007, p. 105.

- ^ Segalstad & Hunter 2008, p. 157.

- ^ Weidman 2011, p. 414.

- ^ a b c Allen, Jim (October 18, 2016). "When the Doors Continued Without Jim Morrison on Other Voices". Ultimate Classic Stone . Retrieved May three, 2019.

- ^ Tayson, Joe (Oct 15, 2021). "The Doors once tried to replace Jim Morrison with Paul McCartney". Far Out . Retrieved Nov 14, 2021.

- ^ Thompson 2009, p. 268.

- ^ Reed, Ryan (May 29, 2015). "2 Out-of-Print Doors Albums Prepped for Reissue". Rolling Rock . Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ "Doors Full Circle Reissue Includes Original Foldout Zoetrope". Ultimate Classic Stone. September 18, 2015. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ "RIAA News Room – Platinum certificates 2001". RIAA. Archived from the original on January two, 2016.

- ^ "Grammy Award Nominees 1980 – Grammy Award Winners 1980". world wide web.awardsandshows.com . Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Iyengar, Vik. "An American Prayer – Review". AllMusic . Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ^ Reed, Ryan (May 29, 2015). "Two Out-of-Print Doors Albums Prepped for Reissue". Rolling Rock . Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ "The Doors with Eddie Vedder Perform 'Roadhouse Blues'". Rockhall.com . Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Stoned Immaculate: The Music of the Doors". AllMusic . Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Baltin, Steve (October 6, 2011). "Remaining Doors Members Record with Skrillex for New Documentary". Rolling Rock . Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ O'Brien, Jon. "Bangarang – Review". AllMusic . Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ "Tech N9ne Works with the Doors". Rolling Stone. June 24, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ Lewis, Randy (February 1, 2016). "Doors surviving members to reunite for Ray Manzarek benefit tribute". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Surviving Doors, Alt-Rock Royalty Gloat Ray Manzarek – Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Feb 13, 2016.

- ^ AllMusic staff. "Buts Band – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Phil Chen – Biography". AllMusic . Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ Goldmine1 (May eight, 2017). "Time CAPSULE: Ray Manzarek, February 12, 1979". Goldmine Mag . Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger of The Doors Tour Dates". Apr 23, 2011. Archived from the original on Apr 23, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Densmore Considers Total Doors Reunion - With Vedder". Contactmusic.com. February 8, 2007. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Ray Manzarek, Founding Member of The Doors, Passes Away at 74". The Doors. Baronial 3, 2013. Archived from the original on Baronial seven, 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "THE DOORS' Robby Krieger & John Densmore To Honor Ray Manzarek at LA Concert! – The Doors". www.thedoors.com . Retrieved May ten, 2019.

- ^ Weidman 2011, p. 418.

- ^ Weidman 2011, p. 421.

- ^ a b Breslin, Rosemary (September 19, 1981). "Jim Morrison: He's Hot, He's Sexy and He's Dead". Rolling Stone. New York City. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2001). Top Popular Albums 1955–2001. Menomonee Falls: Record Enquiry Inc. p. 247. ISBN0-89820-147-0.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2002). Rock Tracks. Menomonee Falls: Tape Research Inc. p. 49. ISBN0-89820-153-5.

- ^ "Video Music Programming". Billboard. New York. January 7, 1984.

- ^ "The Doors a Billboard Chart History". Billboard . Retrieved Dec xv, 2021.

- ^ "Oliver Stone and The Doors". The Economist. March 16, 1991.

- ^ Riordan & Prochnicky 1991, p. 311.

- ^ Broeske, P (March x, 1991). "Stormy Passenger". Sun Herald.

- ^ Fong-Torres 2006, p. 233.

- ^ Cherry, Jim (January 11, 2017). "January 12, 1993: The Doors Enter the Rock & Curl Hall of Fame". The Doors Examiner, Redux. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved Oct viii, 2017.

- ^ a b c Grammy Hall of Fame Archived July seven, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Santa Monica, CA: The Recording Academy. Accessed October 8, 2017.

- ^ "VH1: 100 Greatest Artists of Stone & Roll". RockOnTheNet . Retrieved October xiii, 2017.

- ^ "VH1: '100 Greatest Hard Rock Artists': i–fifty 1–50 – 51–100 (compiled by VH1 in 2000)". RockOnTheNet . Retrieved October eleven, 2017.

- ^ "VH1: '100 Greatest Rock Songs' (compiled by VH1 in 2000)". RockOnTheNet . Retrieved October eleven, 2017.

- ^ "The RS 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". December 9, 2004. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ Fong-Torres, Ben (May 15, 2017). "A Tribute To The Doors". GRAMMY.com . Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ^ "The Doors Honored With Star on Hollywood Walk of Fame". Fox News. Associated Printing. February 28, 2007. Retrieved October eleven, 2017.

- ^ "Grammy Awards 2011: Winners and nominees for 53rd Grammy Awards". March 12, 2014. Retrieved Oct xiv, 2017. Note: scroll to very lesser for "Best Long Course Music Video".

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. May 31, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Kielty, Martin (Nov five, 2014). "Allman, Doors, Metallica, Queen win Archetype Rock Awards". Classic Rock . Retrieved Oct 14, 2017.

- ^ "New Entries to National Recording Registry". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Doors: London Fog 1966". AllMusic. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (Dec 29, 2017). "Doors Plot 50th Anniversary Commemoration in Los Angeles". Rolling Stone . Retrieved Jan 3, 2017.

- ^ "» Doors Go the Sign and the "Twenty-four hours of the Doors" – Venice Update". Veniceupdate.com . Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ "Asbury Park Music Moving-picture show Festival Winners". Thedoors.com. May 1, 2018.

- ^ "The Doors – Morrison Hotel (50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition) Listed Among the All-time Box Sets of 2020". Rolling Stone. December 17, 2020 – via Thedoors.com.

Sources [edit]

- Cherry, Jim (March 25, 2013). The Doors Examined. Bennion/Kearny. ISBN978-1909125124.

- Davis, Stephen (2005). Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend. New York: Gotham Books. ISBN978-1-59240-099-7.

- Debolt, Abbe A.; Baugess, James South. (December 2011). Encyclopedia of the Sixties: A Decade of Civilisation and Counterculture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN978-0-313-32944-ix.

- Densmore, John (1990). Riders on the Storm: My Life with Jim Morrison and the Doors. Delacorte Printing. ISBN978-0-385-30033-nine.

- Einarson, John (2001). Desperados: The Roots of State Rock. Cooper Square Press. ISBN978-0-8154-1065-2.

- Fong-Torres, Ben (Oct 25, 2006). The Doors. Hyperion. ISBN978-1-4013-0303-vii.

- G. Gaar, Gillian (July 8, 2015). The Doors: The Illustrated History. Voyageur Press. ISBN978-0760346907.

- Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 1" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- Hinman, Doug (2004). The Kinks: All Day and All of the Night. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN0-87930-765-10.

- Hogan, Peter G. (1994). The Complete Guide To the Music of the Doors. Music Sales Group. ISBN978-0-7119-3527-3.

- Hopkins, Jerry; Sugerman, Danny (1980). No One Here Gets Out Alive. New York: Warner Books. ISBN978-0-446-97133-1.

- Manzarek, Ray (1998). Light My Fire: My Life With the Doors. New York: Putnam. ISBN978-0-399-14399-1.

- Matijas-Mecca, Christian (2020). Heed to Psychedelic Rock! Exploring a Musical Genre. Hardcover. ISBN978-1440861970.

- Olsen, Brad (2007). Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations. San Francisco: CCC Publishing. ISBN978-1-888729-12-2.

- Riordan, James; Prochnicky, Jerry (1991). Break On Through: The Life and Decease of Jim Morrison. Quill. ISBN978-0-688-11915-vii.

- Segalstad, Eric; Hunter, Josh (2008). The 27s: The Greatest Myth of Rock & Roll. Berkeley Lake, GA: Samadhi Creations. ISBN978-0615189642.

- Thompson, Dave (2009). Your Pretty Face Is Going to Hell: The Unsafe Glitter of David Bowie, Iggy Pop, and Lou Reed. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN978-0879309855.

- Ursula Dawn Goldsmith, Melissa (2019). Listen to Classic Rock! Exploring a Musical Genre. ABC-CLIO. ISBN978-1440865787.

- Wall, Mick (October xxx, 2014). Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre: A Biography of The Doors. Hachette United kingdom. ISBN978-1409151258.

- Wallace, Richard (September 18, 2010). The Lazy Intellectual: Maximum Knowledge, Minimal Effort. Adams Media. ISBN978-1-4405-0888-2.

- Weidman, Rich (October 1, 2011). The Doors FAQ: All That'southward Left to Know Virtually the Kings of Acid Rock. Rowman & Littlefield.

Further reading [edit]

- Ashcroft, Linda. Wild Child: Life with Jim Morrison. Hodder & Stoughton Ltd, 1997-8-21. ISBN 978-0-340-68498-half dozen

- Jakob, Dennis C. Summer With Morrison. Ion Drive Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-0-9817143-8-seven

- Marcus, Greil. The Doors: A Lifetime of Listening to 5 Mean Years. PublicAffairs, 2011. ISBN 978-1-58648-945-8

- Shaw, Greg. The Doors on the Road. Charabanc Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-7119-6546-i

- Sugerman, Danny. The Doors: The Consummate Lyrics. Delta, October 10, 1992. ISBN 978-0-385-30840-3

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Doors

Enviar um comentário for "Behind Closed Doors the American Family S01e05 Vodlocker"